I love German wines. It's bad, really bad. If this was high school I'd be scribbling, “Justin loves Riesling,” in the margins of all my notebooks and have a picture of the Mosel valley taped to the inside of my locker. Despite my not-so-secret crush, we haven't had much success with German wines here at The Chopping Block. Every time I even suggest Riesling, people act like I just asked them to drink a warm glass of simple syrup. Philistines.

Recently, however, we found an unlikely compromise in the form of German rosé. So, now, I get to scream my love from the rooftops and share the blog post I've wanted to write for more than a year. Here's my quick guide to understanding German wine.

In many ways, German wine is similar to that from any major wine producing country. There are three major factors that define any wine growing region and, in this case, a fourth that is distinctly German.

1. Terroir

Each wine producing region has it's own unique terroir, which is loosely defined as the geographical factors that impact viticulture. Germany is defined by its steep slopes and cool climate. In many ways, it is the prototype for cold weather wine production. Their success has demonstrated to other cold regions that quality wine may be consistently produced. In regions such as this, it can be difficult for grapes to fully ripen, vineyard sites are often chosen based on how well they can utilize available sunlight. Stony, south facing, slopes are ideal for providing grapes with more sunlight exposure and heat retention.

2. Grapes

Grape selection is also key for producing wine in cool regions; not all grapes are able to fully develop in cool climates, and those that do are not always capable of making quality wine. Germany has found success with Riesling, with which it is most commonly associated, but there are several grapes grown throughout the country which are equally capable of producing interesting wines. While Germany's reputation is for quality white wine, it's reputation for red wine is growing.

Riesling – This is an old grape with an affinity for cool weather that is incredibly food friendly, capable of making complex wines at every degree of sweetness, and is one of the most commercially successful wine grapes in the world. Like I mentioned at the beginning of this post, I'm going to marry it one day.

Silvaner – This was once a very important grape for German wine production, though in recent years it has fallen out of fashion. Varietal wines made from this grape are generally shipped in distinct bocksbeutel bottles.

Müller-Thurgau – Developed by a Swiss vine breeder, named Hermann Müller, who was from Thurgau (get it?), this is a cool weather grape capable of producing high yields. It does not have a strong reputation for quality wines.

Grauburgunder – This is the grey-skinned color mutation of Pinot Noir that is responsible for those incredibly chic white wines out of Italy. In France it's Pinot Gris, in Italy it's Pinot Grigio, and in Germany it's grauburgunder (grau = grey, burgunder = Burgundy).

Weissburgunder – This is the light-skinned color mutation of Pinot Noir that makes those lovely Alsatian wines I'm cheating on Riesling with. If you're paying attention to the theme from above, this grape is also known as Pinot Blanc, or in weissburgunder in German (weiss = white, burgunder = Burgundy).

Dornfelder – A German red wine grape that was developed in the mid 1950's. It has found success in its home country, but not elsewhere.

Spätburgunder – While it is sometimes called “schwarzburgunder,” Pinot Noir is much more commonly referred to as spätburgunder in Germany. My limited understanding of the language leads me to understand “spät” means late in German, which is paradoxical since Pinot Noir is generally considered an early budding and early ripening grape (apparently not early enough).

3. Regions

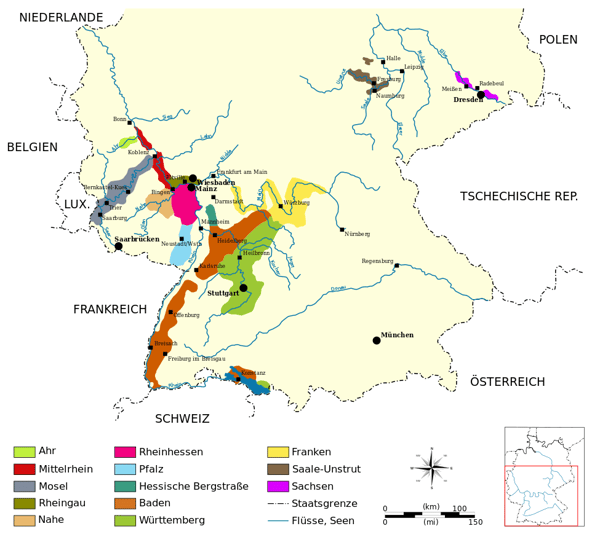

There are 13 major wine producing regions in Germany. Most of the wine I find comes from Mosel, though I've encountered wines from Nahe, Pfalz, and Rheinhessen. Unlike other Old World wine producing countries, I have never seen German wines divided by region in stores. At this time, I simply do not think we see the volume of wine imported from all regions that would necessitate this kind of categorization.

However, I do think it's important for wine to have a sense of place, so for those who are curious, here are Germany's 13 wine regions:

- Ahr

- Baden

- Franken

- Hessische Bergstrasse

- Muttelrhein

- Mosel

- Nahe

- Pfalz

- Rheingau

- Rheinhessen

- Saale-Unstrut

- Sachsen

- Württemberg

4. Wine Labeling

The most misunderstood part of German wine is how it is labeled. There are 2 levels of categorization for German wines, the first is pretty familiar, almost identical to French labeling. Last October I wrote a blog outlining how to read a wine label, at this level all of that information is still applicable.

Landwein = land wine/ table wine

Qualitätswein = quality wine, similar to the French “vin de pays.”

Prädikatswein = this is the highest quality German wine that is further subdivided into 6 categories based on must weight, essentially the concentration of sugars is measured in degrees Oechsle in the unfermented grape juice. In other words, the longer grapes are allowed to ripen the more sugar they are capable of producing, so, these additional six categories give some indicated of the ripeness of the grapes at the time they were picked.

Kabinett (67-82°) - This is the lowest end of the spectrum based on must weight and, in general has the smallest amount of sugar. That being said, Kabinett wines come in varying degrees of sweetness and can range from bone dry to medium sweet.

Spätlese (76-90°) - Literally translates as “late harvest,” these wines can range from dry to medium sweet.

Auslese (83-105°) - Literally translates as “selected harvest, at this level it is not uncommon to find grapes affected by botrytis cinerea (a beneficial fungus that concentrates sugars). These wines can range from dry to sweet.

Beerenauslese (110-128°) - Literally translates as “berry selection,” at this level it is more common to find grapes affected by botrytis cinerea. Wines produced at this level of Prädikat are only sweet.

Trockenbeerenauslese (150-154°) - This level of must weight can only be achieved by grapes affected by botrytis cinerea. Obviously, these wines are only sweet.

Eiswein (110-128°) - Literally translates as “ice wine.” This is something of an exception to the other Prädikat wines; the must weight requirements are the same as Beerenauslese, but in order for a wine to be classified as Eiswein the grapes must be allowed to hang on vine so long they are affected by frost, freezing the water inside the grape and separating it from the sugars. Once again, these wines are only sweet.

I've joked in several posts about how reluctant people are to try sweet wines, to make the point bluntly, if you haven't tried one of these last three Prädikat, you've never had a sweet German wine.

That being said, if you simply can't stand the thought of residual sugar in a wine, look for one of the first three Prädikat descriptions, the higher the alcohol content on the label, the less likely there is for any residual sugar. If you're lucky you might encounter a bottle like this rosé that comes right out and tells you it's dry, in this case indicated by the word “trocken.”

Explore wines from all over the world in our wine classes. Stop by our stores to pick up a bottle of this German rosé, which is quickly gaining in popularity. I'd be happy to share a taste with you!