Conventional wisdom tells us a lot of things when it comes to cooking: searing meat seals in the juices, salt your water to make it boil faster, don’t cut raw meat on a wooden cutting board, add oil to your pasta water to keep noodles from sticking, don’t wash mushrooms, and if you’re serious about cooking you should use unsalted butter.

We have all heard these so many times before, and believe it or not they also happen to all be demonstrably false. For this post we’re going to take a cool refreshing deep dive into that last one: unsalted butter.

Most of the other claims listed above have been long debunked, but there are still thousands of unfortunate souls roaming the land, lips slick with butter grease that is but a pale whisper of what it could be. So why do we even care about this? Unsalted butter? So what? You don’t like it put some salt on top and move on you pedantic piece of human garbage. Well, hang on a second there. It’s not quite that simple. At what point you salt the butter actually matters a lot. Salted butter is usually salted right after the butter has been churned, when you are kneading it and rinsing it to wash out the whey and make the butter mass homogenous. Adding the salt at this point in the process means the salt is fully dissolved and distributed throughout the butter. For this reason, salted butter tastes like what butter was meant to be. In the same way salt turns up the volume on flavors in savory dishes when applied in the right amount, so too does it amplify butter’s intrinsic butteriness. We call this ‘proper seasoning’ and cooks are obsessed with it, except, bafflingly, when it comes to butter. Try to add salt to unsalted butter, however, and it tastes like just that, bland butter with salt on top.

So why did we start using unsalted butter in the first place? The standard rationale goes something like this: You should use unsalted butter because you want to be able to control how much salt you add to your dish. This undeniably makes sense. It’s true that you want to be able to control the salt in your food, and unsalted butter offers you more control over the salt in your food, but there is a lot going on under the surface of this argument so let’s—as they say—unpack it.

First, this argument seems to suggest that the amount of salt in salted butter is so high that using it in place of unsalted butter would render the cook unable to add seasoning of any kind, and, in fact, would by itself render the dish too salty. Additionally this line of thinking assumes that high resolution control of seasoning is a virtue higher than deliciousness or that control of seasoning must lead to maximized deliciousness. But is this all true? It seems the real question here is how much control over seasoning do you gain by using unsalted butter, and is it worth the cost of delicious flavor?

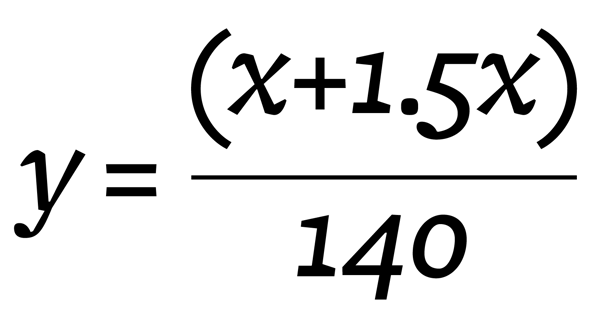

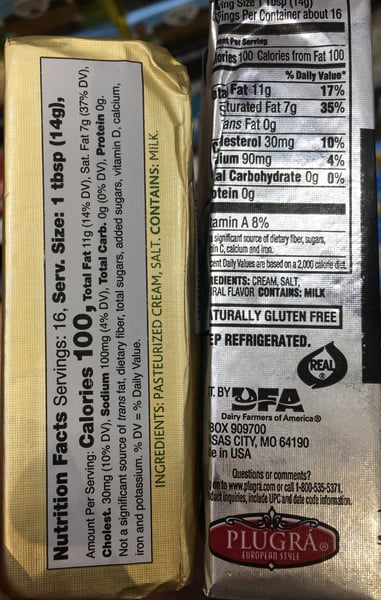

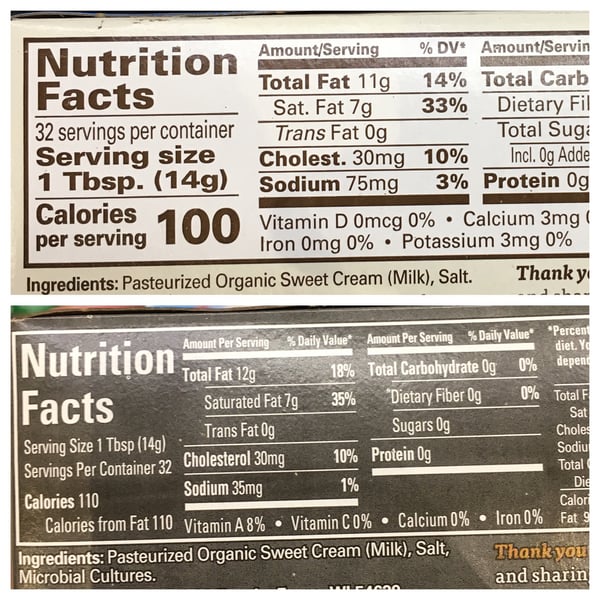

Another facet of the pro-unsalted argument is that you should use unsalted butter because you don’t know how much salt the company making it has added. This is kind of true. Different brands do add different amounts of salt to their salted butter, but this is a problem that’s easy to solve. Why? Because companies are legally required to tell you how much sodium is in their product, and we know math. All we have to do is take the amount of sodium per serving specified on the nutrition facts label, add 150% of that number (because salt is only about 40% sodium by weight), divide that number by 1000, then determine what percentage of the serving is salt. Sounds complicated? Well I wrote you an equation to make it easier: where x is the milligrams of sodium specified per 14 g serving (they all use this serving size), and y is the percentage of salt per any given weight of butter. Pretty cool, right? No? Well I think it’s cool.

Most foods we eat that are considered “properly seasoned” clock in at between 1.5-2.0% salt by weight (you’ll have to take my word for it, but it’s true), and we can plug in the nutrition info for the butters pictured below (a good representation of the salted butters that you are likely to encounter: Plugra, Kerrygold, Organic Valley salted, and Organic Valley Cultured) to discover that most all salted butter is between 1.3-1.8% salt by weight.

This means most all salted butters fall under our description of “properly seasoned.” That means that just eaten by itself salted butter is not egregiously salty. Thus it stands to reason that unless your dish is already too salty, it is physically impossible to over-season it with salted butter.

The anti-salted argument also starts to sound a little silly when you try to extend it to non-butter ingredients. For instance, no cook would ever tell you to use unsalted Parmesan cheese, or unsalted soy sauce, or unsalted pickles, or unsalted Prosciutto, or unsalted miso. So why unsalted butter? Furthermore, let’s try examining the idea that you can add salt to something at any point in its production and yield the same result. By this logic we should be able to cook a steak totally unseasoned and add salt only after its been sliced, and have it taste the same as a steak that was seasoned before it was cooked. An idea that—I promise you—exactly zero pro-unsalted cooks would agree with.

Strong as I feel this argument is I didn’t write this to convince you to use salted butter for only your savory dishes. So what about pastry? What about products that can’t really read as salty on the palate at all? Well I had this concern too, and leaving aside the fact that most pastry recipes use too much sugar and not enough salt as it is I wanted to do a test to see if salted butter held up under these conditions. So I tried to think of a recipe that was almost entirely butter by weight, and would come off weird if it tasted even a little salty. I settled on buttercream frosting. I used the following recipe to yield my unflavored base, then folded in some seasoned (with salt) strawberry rhubarb jam to flavor it.

Basic Salted Buttercream

- 75 grams egg whites (about two whites)

- 183 grams granulated sugar split into 150 grams and 33 grams (about 3/4 Cup, and 2 1/3 tbsp sugar respectively)

- 42 grams water (about 3 1/3 Tablespoons)

- 227 grams salted butter at room temperature (two sticks)

- Place egg whites in the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the whisk attachment.

- Combine 150 grams sugar and water in a saucepan and bring to a simmer.

- Cook sugar syrup to 230 degrees F. Once this temperature is reached start whipping the egg whites, gradually adding the 33 remaining grams of granulated sugar until the whites reach soft peaks.

- When the sugar syrup reaches 248 degrees carefully pour it between the whisk and the side of the bowl with the mixer on medium.

- Whip the egg whites for about 15 minutes until the bottom of the bowl is room temperature to touch.

- Add the room temperature butter one tablespoon at a time until it is fully incorporated.

- You’ve done it! Flavor as you like.

When the buttercream was totally plain, it came across as lightly salted sort of how a good salted caramel tastes. Still definitely dessert, and honestly pretty delicious, but I wanted to see how it tasted with a flavor because only a complete sociopath would use completely unflavored buttercream. Once I had added other flavors the perception of salt totally dropped away, and left only a delicious frosting that I used to frost a chocolate cake (which was also made with salted butter). Was it the most delicious buttercream I’ve ever had? Well, actually yes. It was.

In speaking to my colleagues at The Chopping Block, I did encounter one compelling reason to use unsalted butter, and that’s for teaching purposes. When a student is first learning new pastry techniques like buttercream it's important to use unsalted butter so that they can focus on the technique itself and not worry about trying to nail seasoning which can be done later (just not as well…). Not to mention basically every pastry recipe you’re likely to encounter in the wild will be dialed in for unsalted butter, but why let our food languish at the hand of the status-quo? Together we can change the recipes. We can usher in a new well-seasoned, full-fat world.

If you enjoy hot takes, and technical deep dives like this (hi, nobody!) you would definitely love any of our more intensive Boot Camp classes where we have the time to really go in-depth into whatever topic we’re covering. They are my favorite type of class to teach, and I hope to see you there!